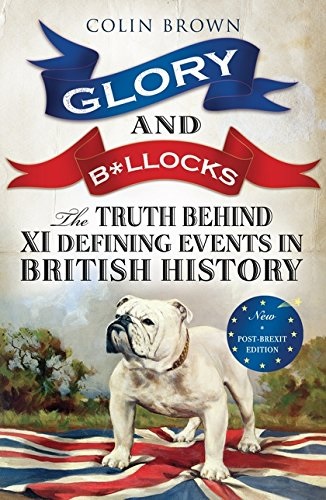

Glory & B*llocks – C. Brown

I don’t know enough about history to know quite what to make of this, except to be suspicious of right wing attempts to control the history curriculum.

I don’t know enough about history to know quite what to make of this, except to be suspicious of right wing attempts to control the history curriculum.

It deals with such issues as : was the technologically sophisticated longbow responsible for the landmark victory at Agincourt, or was it simply that the English are better in mud? When did Queen Elizabeth I learn that the Armada had capitulated – before or after she delivered one of history’s most inspiring and self-serving speeches? Why did Wellington meet his Waterloo on his return to London?

I had to look up ‘phaeton’ = a horse-drawn sporty open carriage

Quotations:

I discovered that, contrary to popular belief, the longbow was not responsible for the English (and Welsh) victory at Azincourt; that Queen Elizabeth I’s great Armada speech at Tilbury was probably an enormous exercise in spin; and that some who campaigned alongside Wilberforce for the abolition of the slave trade saw him as a hindrance rather than a hero of change. As I reflect in the Postscript, I was also reminded strongly how important that strip of sea between Dover and Calais really is. I was also surprised to find that, despite that natural fortress, we have been successfully invaded at least twice since 1066 — in ‘2’6 as well as in 1688.

The Victorians poured more scorn (and worse) over the head a sullied John, while polishing the image of their glistening hero. And they wilfully ignored the truth about Richard: far from being dedic to England, he only spent six months of his reign in the kingdom, si French not English, and squeezed as much money as he could fron people to finance the Crusades. He once even said he would have London, if he could have found a buyer. Richard set ‘new standard royal rapacity’, according to the historian Geoffrey Hindley.

John undoubtedly got a bad press from the monkish chronic of his day because of his seizure of Church assets. Tudor histor portrayed John in the mould of Henry VIII, who defied the Pope was destroyed by traitors around him.

In 201r, a campaign was launched on the Government’s e-petition wd to have Richard’s statue removed, because of the injustices he meted ot Muslims during his reign — three thousand were slaughtered outside the of the city of Acre alone. But the legend is hard to dent. In its first days petition collected a mere seven signatures.

Magna Carta had protected the civil liberties of the medieval elite, but Coke ingeniously asserted that it guaranteed individual rights to everyone, of every station.

The first myth was about numbers. Henry’s historians exaggerated the scale of his ‘miraculous’ victory at Azincourt, to show that Henry must have had God on his side. And the dispute about the size of the opposing force still rages today.

The second myth was about the longbow. English victory was secur by a remarkable feat of arms, but there is much compelling evidence show it was the archers ‘bollock daggers’, axes and hammers that inflict the damage, not the longbow.

Finally, there is the myth of Henry V himself. Victory at Azincourt changed everything in Henry’s lifetime. He returned a hero, with his on the throne of England strengthened and his hold on his disputed possessions in Northern France consolidated. The death of so many French nobles paved the way for Henry to conquer Normandy within years of Azincourt. It gave the English control of large swathes of France, including Paris, for a generation.

`Like so many of Elizabeth’s actions,’ the historian Neil Hanson suggests: ‘the Tilbury appearance had been pure theatre, mere show, and the speech to her forces that has echoed down the ages was a sham, delivered r the danger had passed.” Historian Susan Frye, who has led the academic charge at the ‘myth’ of Elizabeth at Tilbury, has cast doubts the authenticity of her great Tilbury speech. ‘No reliable eyewitness account exists of what Elizabeth I wore or said,’ she wrote.’

Any journalist who has covered prime ministerial visits to the war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan can testify, however, that political leaders often deliver different versions of the same speech over a two-day visit. As one who has frequently covered such events, I find it unsurprising that several versions of Elizabeth’s remarks have been attributed to her. That should not mean that they were not delivered. She clearly made several pep talks to her men at Tilbury during Thursday and Friday, 18 and 19 August.

After all, the Spanish had arranged for a Catholic fanatic to assassinate the Protestant leader of Flanders, the Prince of Orange, in his own home in Delft only a couple of years before, and Pope Pius V in 157o had issued a papal bull encouraging Catholics to kill the rebel Queen, like a fatwa against her life. It was renewed by Pius’s successor, Pope Sixtus V.Thousands of printed copies of his papal bull calling upon her subjects to depose her were put on board the ships of the Armada for distribution when they landed.

Elizabeth was a genius at public relations for her own age. She nee to be, to survive the forty-five years of her long reign. Towards the with the population growing sharply from three million to four poverty increased and her Government responded by creating the state support for the poor, to damp down the threat of rebellion or riots. She dealt decisively with direct threats — even her favourite, Earl of Essex, went to the block after raising a rebellion against her she was a consummate politician. She was acutely aware, partic a woman, that she could only rule with the consent of her people. was careful to placate her Parliament — in her last address to Parliament in 1601, known as her ‘Golden Speech’, she said: ‘There is no je of never so high a price, which I set before this jewel; I mean your love.

Elizabeth helped to create a Britain that is recognizable today independent nation, fierce in its defence of its identity. The defeat Spanish Armada in 1588 was truly one of the great landmarks of history. If her speech was a sham, I cannot help asking: so what?

Margaret Thatcher, then Conservative Prime Minister, put forward that rosy gloss on history in the 1988 Commons debate for the tercentenary of the Glorious Revolution. It had, she said, secured ‘tolerance, respect for the law and for the impartial administration of justice, and respect for private property. It also established the tradition that political change should be sought and achieved through Parliament. It was this which saved us from the violent revolutions which shook our continental neighbours and made the revolution of 1688 the first step on the road which, through successive Reform Acts, led to the establishment of universal suffrage and full Parliamentary democracy.’This fable has held for nearly three centuries. But she was speaking before her own hold on power was violently shaken by street riots in London against the poll tax in March 199o, which ultimately led to her downfall.

Tony Benn, then Labour MP for Chesterfield, rejected this version of events: ‘What happened in 1688 was not a glorious revolution. It was a plot by some people… to replace a Catholic king with another king more acceptable to those who organized the plot… Nor was 1688 the establishment of our liberties… Are we to welcome a Bill of Rights that says that papists could not sit in either House of Parliament?’

It is difficult to disprove Benn’s argument by showing that the over throw of James II by William III was a ‘popular’ uprising. In the absence of seventeenth-century opinion polling, there is no conclusive evidence either way to show what the ‘man in the street’ of Stuart England re thought about the arrival of William III. There were, of course, pock of Protestant protest, in Hull and in the West Country, in support William. The eye-witness reports suggest that William’s march from Brixham was welcomed by the general public in the towns thro which he passed, but behind the colourful show was a serious arm

In fact, William was so disappointed by the failure of more Ian gentry to join his banner in the first few days that he threatened to go to Holland. This gives credence to the claim by the Left that it was a by an elite of the landed classes. But that is not the whole story — J alienated Parliament, academics, lawyers and, fatally, the commanders of his army, particularly Churchill, who swung behind William. James found that juries would not convict those he accused of refusing to his pro-Catholic edicts. And we have Evelyn’s diary evidence that people prayed for deliverance from their Catholic King with a Protestant wind.

It is hardly unexpected that many ordinary people did not join his army. the West Country the trials that followed the Monmouth Rebellion e a recent reminder that they could end up on the gibbet if they joined other rebellion that did not succeed.

David Starkey has persuasively argued that William was the first mod-monarch. In his own country William was a Stadtholder, a ruler of the Dutch states but not a sovereign. William, acting like a chief executive for England plc, brought over to Britain some of the modern economic innovations which had made the Dutch a great trading nation, such as public borrowing and the creation of the Bank of England. This led to steep growth in Britain’s overseas trade and its status as a world power.

This was the part of the Revolution that was truly ‘Glorious’ for Britain. William also brought Britain into a stable alliance with the Protestant Netherlands, enabling him to challenge the power of France and change the balance of power across Northern Europe. In conceding a constitutional monarchy, he stripped away some of the mystery of royalty. He abandoned the practice of touching the sick for the ‘King’s Evil’, or scrofula (a swelling of the lymph glands caused by tuberculosis), a practice that had been revived by Charles II at the Banqueting House in Whitehall.

The coronation of William and Mary was quickly followed by constitutional reforms with a Bill of Rights, curbing the powers of the monarch for ever; the Triennial Act ensuring Parliament was automatically summoned every three years; and the introduction in 1697 of the Civil List, giving Parliament control over the royal expenditure as well as the raising of all revenue for the armed forces. However, as a Commons Library paper points out, the ‘Bill of Rights’ is a misnomer. It is not like the United States’ written constitution, nor does it set out individual rights. It was rushed onto the statute book to give legal force to the removal of James II for misgovernment, and then to settle the line of accession through the descendants of William and Mary, then through Mary’s sister Princess, Anne and her descendants. The bill was designed to curb future arbitrary behaviour of the monarch, and to guarantee Parliament’s powers over the Crown, thereby establishing a constitutional monarchy.’

philanthropic Acts of Parliament in British history was born out of a political fix by William Pitt to keep Fox at bay.

Wilberforce answered the case perfectly: he possessed the passion and patience to pursue the campaign in Parliament through setbacks and s, knowing full well he had Pitt’s support and counsel behind the scenes. The young Prime Minister knew Wilberforce was just the man. After his religious awakening, Wilberforce had threatened to give up politics altogether and, having become sickened by gluttony (Pitt was the habit of regularly drinking three bottles of port at a sitting, and re were lavish banquets to attend as an MP) and sin (Wilberforce bled at cards at Boodle’s and may have once visited a brothel), he had also threatened to cut himself off from his former friends. Wilberforce igned from his clubs — Boodle’s, Brooks’s, White’s and Goosetrees — Id a racehorse, cut down on his partying and limited his wine intake to o more than six glasses a day. Pitt, however, persuaded him not to give up his friends and his seat in the Commons.

At the time of his great personal crisis, Wilberforce also sought the advice of a charismatic preacher, John Newton. He was as unlikely a priest as it was possible to imagine, more an old sea-dog than dog-collar wearer. Newton had spent most of his life at sea, both in the navy after being press-ganged and serving on slaving ships. He was a former slave-ship captain himself, but had gradually undergone a conversion to God. It was only after a stroke that he gave up the sea and sought a new life as a priest. Newton had been accepted into the Church of England — after great difficulty — and had become renowned as an Evangelical preacher and composer of hymns

Wilberforce had go cautiously to maintain his own coalitions of support for abolition at Westminster.

Two days later, while recuperating at his home at the King’s racing stables at Newmarket, ones received a telegram from Buckingham Palace. It had been sent by a palace flunkey on behalf of Queen Alexandra, the Queen Mother. ‘Queen Alexandra was very sorry indeed to hear of your sad accident caused through the abominable conduct of a brutal lunatic woman. I telegraph now by Her Majesty’s command to enquire how you are getting on and to express Her Majesty’s sincere hope that you may soon be all right. Wighton Corbyn.’

Jones’s psychological wounds went far deeper than his physical ones. No one ever suggested Davison’s death was his fault, but Jones attended the funeral and claimed he was haunted by her face for the rest of his life. In i 95 t, he switched on the gas in his kitchen and took his own life. He was seventy-nine.

Had she lived, Davison would have been prosecuted for injuring the jockey. In the Home Office files, I find a memorandum to the Liberal Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, which is brutally unfeeling. McKenna was a banker, and politically out of his depth in dealing with the delicate problem of the suffragettes. The note, written as Davison lay dying, reads: ‘The D of PP [Director of Public Prosecutions] says that if Davison recovers, it will be possible to charge her with doing an act calculated to cause grievous bodily harm to the rider of the horse.’ One is tempted to ask, what about the horse? Perhaps she should be prosecuted for that too.

The Pankhursts may have found it difficult to control Davison while she alive, but they made full use of her after her death.

Emmeline Pankhurst knew the value of propaganda. She even lied ut her own birthdate to enhance her image as a revolutionary — she frequently spoke about the inspiration she drew from being born on 24 y, Bastille Day, but her birth certificate shows she was born a day later.

In seeking a successor to lead Britain in its hour of need, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, later the Queen Mother, would have preferred the cool-headed (some said cold) Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, to the headstrong Churchill. But the aesthete Halifax (sometimes called the ‘Holy Fox’ for his love of hunting and his religious piety) was an architect of Chamberlain’s appeasement policy, and in May, the King and Queen still favoured appeasement; it was only during the Blitz that George VI and the Queen came to embody the British spirit of resistance. The deciding factor, however, was Labour’s refusal to work in a coalition under Halifax.

Halifax had enough self-awareness to acknowledge that he could not hold the country together for war.

Weapons like something out of Heath Robinson cartoons were imagined, and then produced. A makeshift tank trap, consisting of petrol tanks that would be exploded over a Panzer tank, was prepared for the main road from the coast at Shooters Hill to London. Nearby, a command headquarters for the resistance movement was established in the basement . Nearby, a command headquarters for the resistance movement was established in the basement of a local house. All over England, road signs and nameplates on station platforms were taken down to confuse the enemy, an idea hatched in Whitehall by occult author Dennis Wheatley, who was part of a ‘black ops’ deception team. It succeeded in confusing everyone.

Many believe the Battle of Britain was an ‘English show’, but it was in fact a multinational effort. In addition to pilots from the colonies, including one Jamaican, there were one hundred and forty-five Polish airmen, eighty-eight Czechs, thirteen French and seven Americans despite being banned from combat by their country’s official stance of neutrality. In this and other covert ways, Cameron was partly right that Britain had a valuable ally in America in 1940.

The switch in Goering’s tactics led to the Blitz on British cities, and the Blitz brought a new terrifying phase of the war, which increased the stoicism of the British people. But it also broke down barriers. One of the first lessons the besieged had to learn was that in war, the English reserve had to go. Everyone ‘mucked in’. They had to get used to being crammed together. Now every street was in the front line.

Beveridge proposed tackling what he called the five ‘Giant Evils’ afflicting society: Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. He proposed improved state education, council housing, a comprehensive national health service and a range of benefits to lift people out of poverty, paid for from a new National Insurance scheme. He also proposed ‘full employment’, with a target of no more than three per cent unemployment (the level is now 8.4 per cent). This was not intended simply as an act of altruism; those who question the cost of the welfare state today should remember that Beveridge believed full employment was the vital component in delivering the taxes that would pay for his proposed social benefits.

The Beveridge report sold one hundred thousand copies month; a special cheap edition was printed for the British forces. The figures were unprecedented and remain unequalled by the HMSO. In Nazi-occupied France, dog-eared copies of the Beveridge report circulated and shared clandestinely by the Resistance. Beveridge subversive because it provided a democratic rejoinder to fascist state ‘alism. In England, the report gave the people something else worth ting for, in addition to their patch of island in the North Sea. Churchill was reluctant to back the plan because he feared the cost uld be unaffordable. The bill for putting Beveridge’s proposals in place was then predicted to tally up to £I00 million (about £3.3 billion at today’s prices). The actual total today is £150 billion — and that is without accounting for the NHS. Diaries, written in a series of exercise books, by Norman Brook, the Cabinet Secretary, of secret conversations inside the War Cabinet reveal Churchill was furious with Beveridge, who wanted to do his own spinning of the report by briefing Parliamentary lobby journalists before its publication. Churchill rightly worried that Beveridge would bounce the War Cabinet into approving his report. The Prime Minister felt he could not allow that to happen.

a key part of the welfare state was built on a lie. Beveridge based his system on National Insurance Contributions (NICs), but universal state pensions were never funded by an insurance fund. State pensioners like to think they are getting back what they paid in over a lifetime of NICs; they have paid their insurance ‘stamp’ and are entitled to draw on the proceeds of their contributions in their old-age. It is a myth.

Beveridge described his new, universal state pension scheme as ‘first and foremost a plan of insurance — of giving in return for contributions benefits up to subsistence levels, as of right and without means test, so individuals may build freely upon it’. He intended that NICs would gradually build up a pot to fund the old-age pension over twenty years. However, the Attlee Government knew that its supporters in 1946 would not wait until 1966 to get the pensions they had been promised after the war; the Government went ahead immediately, by raiding the contributions, without waiting for the fund to mature. That meant a key component of the welfare state, the state pension, was founded as a pay-as-you-go scheme rather than as Beveridge had outlined, as fully funded insurance.

Entitlement to state pensions requires NIC payments, but the state pension is in effect a massive, national Ponzi fraud.* Today’s state pensioners are relying on the contributions of the people in work today; their own contributions have been spent on earlier generations of pensioners, and so today’s state pensioners are taking their benefits from the pensioners of the future. No one has called in the fraud squad so far because the contributions have kept rolling in. No political party is brave enough or stupid enough — to call a halt to this con trick. But with an ageing population, and a decreasing number of workers paying taxes to pay for their pensions, one day it may unravel.

- Charles Ponzi, an American fraudster in the 192os, paid investors dividends from new investors, rather than from profits earned on stocks.

One of the best-kept secrets of the 1939-45 conflict is the number of strikes that took place while Britain was fighting the war. There were nine hundred strikes in the early months of the conflict, partly because communists in Britain refused to be bound by the calls for national unity until the Soviet Union allied with Britain in 1941. Bevin, a natural autocrat, responded by using emergency powers to ban strikes in the pits, in the factories and at the docks. He also upset Britain’s miners by ordering one in ten of those conscripted to fight, to go down the pits instead. Known as the `Bevin boys’, these conscripts stirred resentment among regular miners, provoking still more strikes. Three union officials were imprisoned and over a thousand strikers fined in the Kent coalfield in 1942. Thefollowing year, twelve thousand bus drivers and conductors, and the dockers in Liverpool, went on strike – a considerable embarrassment for Bevin because they were largely members of the Transport and General Workers’ Union.’4 In 1944, the strikes reached their peak, with over two thousand stoppages.

When Bevin introduced tougher anti-strike laws to settle the nation’s wartime production, Bevan fired back with a Commons rebellion. The Minister for Labour, he said, had provoked the strikes through ‘incompetence’. Immediately, Bevan was threatened; if he continued to criticize the anti-strike laws he would be kicked out of the party. He wisely avoided making himself a martyr. He was popular with the constituencies, and was running for a seat on Labour’s National Executive, which would give him more influence. And he won. That meant Attlee had to come to terms with the Welsh rabble-rouser.

Comments are closed.